The Language Politics Behind Heart Lamp

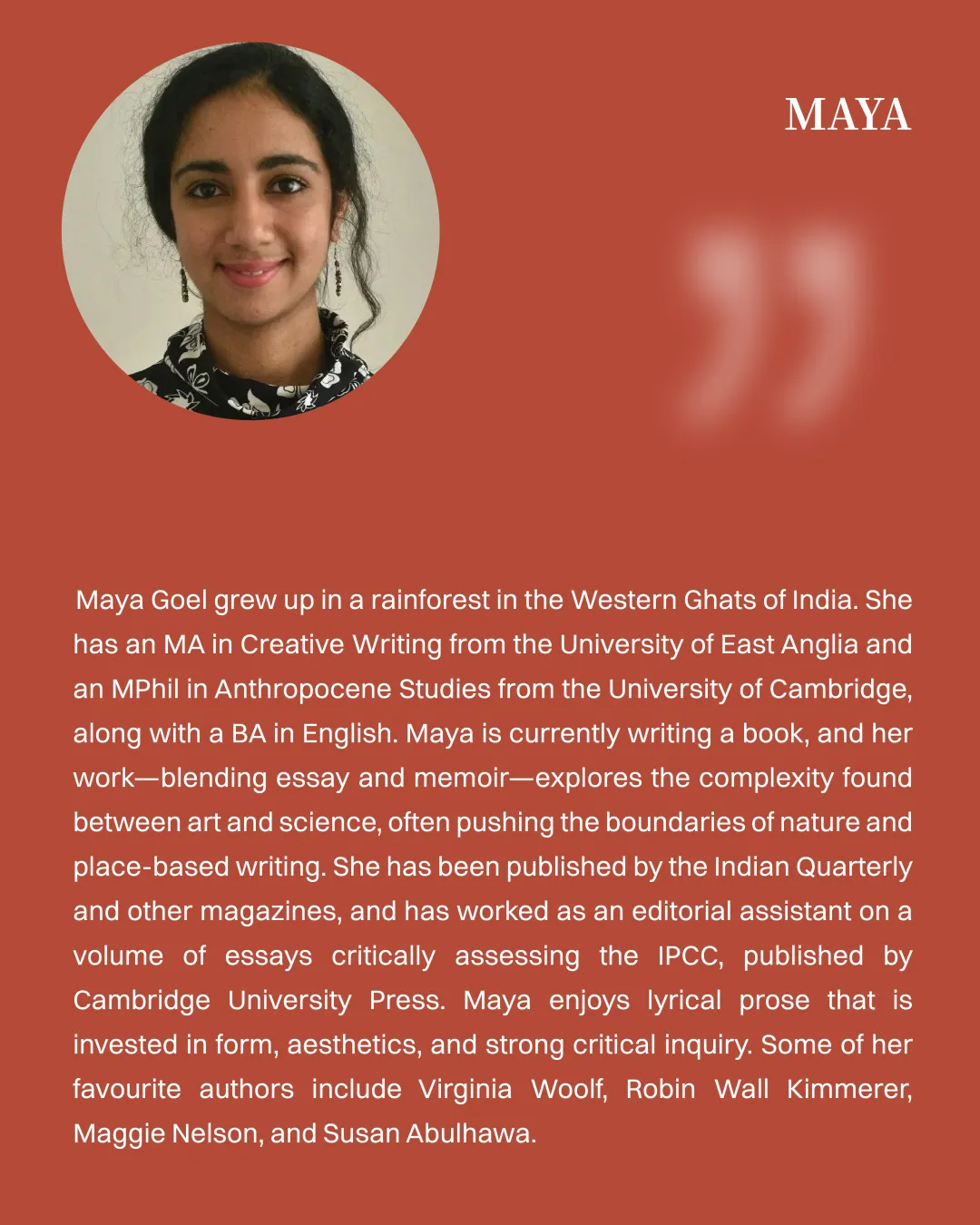

Maya Goel

edited by Leah

This year, on the 20(th) of May, the International Booker Prize was awarded to Heart Lamp, a collection of stories written in Kannada by Banu Mushtaq and translated into English by Deepa Bhasthi. The news swept through Indian literary circles, creating a ripple of excitement. It was an extraordinary event, not because the author was from India, but because this was the first time such international recognition had spotlighted a book written in Kannada.

Kannada belongs to the Dravidian family of languages spoken across South India. It is the official language of Karnataka, a state nestled between Kerala (where they speak Malayalam), Tamil Nadu (where Tamil is spoken), and Andhra Pradesh (where the language is Telugu.) I live in Karnataka, and my friends from all over South India were thrilled about the award’s recognition of Kannada literature – whether or not they spoke Kannada. This is because the event marked an acknowledgement of the Dravidian linguistic culture that represents half the subcontinent, yet often gets sidelined by the dominance of the North.

Heart Lamp is a collection of stories about women. The stories are situated in the Muslim community and weave a rich tapestry of their lives, relationships, and multifaceted struggles. Despite being grounded in these specificities, they also speak to a broader experience of womanhood, resonating with voices raised against patriarchal oppression across the world.

Alongside being a writer, Banu Mushtaq is also a lawyer and activist. Mushtaq began writing in progressive literary circles in the 1970s and ’80s. She belonged to the Bandaya Sahitya movement, which was critical of the class and caste systems, and gave rise to a number of influential Dalit and Muslim writers. Mushtaq was one of the few women among them. In Kannada, she has written a novel, six short story collections, an essay collection, a poetry collection, and won major awards in Karnataka. Her work is significant not just for its literary acclaim, but for the role it plays in a charged political climate.

With the rise of the far-right BJP-led government in India since 2014, there has been a powerful clampdown on freedom of speech, academic institutions, social activism, and increased oppression of religious minorities. In an environment that fosters divisive tactics and communalism, Muslim voices have been systematically suppressed. To have a Muslim woman honoured in the literary sphere makes a significant mark in their visibility.

Apart from religious divides, another controversy that has heated up in recent years is language imposition. India has hundreds of regional languages (estimates vary between 780 and 1,600) and thousands of dialects. However, since Independence, there has been a push to make Hindi the sole national language of India. Indian nationalists have long promoted Hindi, and it has displaced dozens of previously existing languages and dialects (such as Bhojpuri, Maithili, Avadhi, Braj Bhasha etc.), becoming the dominant language in the North. Pre-independent India was also marked by a political struggle between Hindi and Urdu, as the former was seen as a Hindu language and the latter as a Muslim one.

Language politics in India is often depicted as a struggle between the North and the South. Attempts to make Hindi the national language for all of India have been met with resistance and protests in the South, primarily Tamil Nadu. While a lot of attention focuses on the perceived clash between Tamil and Hindi, other South Indian states like Karnataka are often ignored in these narratives.

Karnataka is a diverse state, containing native linguistic minorities like the Tulus and Kodavas, as well as populations of Marathi, Telugu and Tamil speakers at the borders, and large immigrant communities. Historically, Tamils used to be the biggest migrant population in Bengaluru, the state capital. But now, North Indians – both middle class professionals drawn to the burgeoning IT sector as well as working class laborers – have become the new wave of migrants. There is a long history of conflict between Kannada-speaking locals and these immigrants. Kannada nationalism is a growing movement, although it hasn’t yet crystallised into a political body. Conflicts between Kannada and Tamil speakers in Bengaluru used to be the main focus, but now anger is increasingly directed towards North Indians and attempts by the central government to push Hindi over Kannada.

Kannada has existed for at least fifteen centuries and is the second oldest of the Dravidian languages prevalent in South India. The study of Indian languages has historically been dominated by Sanskrit, the progenitor of many Indo-Aryan languages spoken in the North, including Hindi. Brahmin (upper-caste) pandits described Sanskrit as the language of the gods. Early British scholarship of the Calcutta School of Orientalists believed all Indian languages to have descended from Sanskrit, and considered it the key to understanding Indian culture. However, this was opposed by the Madras School of Orientalists, formed by British administrators and scholars in the then Madras Presidency in South India. In 1816, the civil servant and scholar Francis Whyte Ellis theorised that the languages of the South - Telugu, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam, Tulu and Kodava shared a common ancestor that was not Sanskrit and was distinct from the Indo-European roots of both Sanskritic and European languages. This was the beginning of what is today considered the Dravidian family of languages, believed to have descended from an older form of Tamil. Kannada belongs to this family, and was given the status of a classical language.

My parents are originally from the North, so my mother tongue should be Hindi, but I grew up with English as my first language. In my locality, people primarily speak Kannada and Kodava, along with some Tulu, Tamil and a scattering of other languages. The town where I live, Madikeri in Kodagu district, also happens to be the home of Deepa Bhasthi, Heartlamp’s translator. When Bhasthi was young, her mother would read Kannada passages aloud to her during exam revision because although she spoke the language, she could not read it fast enough. My own Kannada is not as fluent as Bhasthi’s, but I can speak it well enough to communicate. I learned to read and write the script in school; however, my abilities are limited because I cannot fully comprehend a book written in Kannada.

Kannada is a diglossic language, meaning that the spoken form varies from the written form. Most Kannada books use a language quite different from the way an average person would speak. This was especially prevalent in the Navya tradition of formal Kannada literature. The Navya writers of the modernist movement that emerged in the 1950s often kept art and literature separate. They were criticized for not understanding social inequalities well enough to deeply interrogate them in their writing. They were preoccupied with the self rather than the community.

The Bandaya Sahitya movement emerged as a radical response. Banu Mushtaq was part of this movement, which sought to rethink Kannada literature by drawing attention to subaltern voices and interconnected communities rather than focusing on individuals. They incorporated elements of spoken Kannada into their writing, which was unheard of in the Navya tradition of formal Kannada. This opened space for protest writing, polemics, community narratives and multi-dimensional characters. Mushtaq’s work has been described as direct and confrontational, rejecting the dominant Sanskritised literary forms.

While Mushtaq’s writing rejects a rarefied version of Kannada, it carries the influences of a number of other languages. One of these is her mother tongue, Dakhni, used predominantly by Muslim communities in South India. Dakhni is a mix of Persian, Dehlavi, Marathi, Kannada and Telugu, and is often (mistakenly) called a dialect of Urdu. Urdu and a few Arabic phrases also pepper Mushtaq’s writing, and Deepa Bhasthi, Heart Lamp’s translator, has tried to convey these elements in her English translation.

Bhasthi writes that she enriches her translations by immersing herself in the culture of the text she is working with. Since Mushtaq’s stories are set within India’s Muslim community, her references were unfamiliar to Bhasthi. Bhasthi bridged the gap by ‘reaching for a culture that shared linguistic, social, and aesthetic influences with the milieu of her stories.’ She was consumed in the world of Pakistani TV dramas, Qawwali music, and opened the notes of her Arabic lessons. Bhasthi is keenly aware of her work’s socio-political nuances and implications. She writes in The Paris Review:

In the hierarchy of who gets to translate, who gets to be translated, who gets funding for new translations … Kannada does not fare too well. Barely a handful of literary translations in the Kannada-English pairing is published in a year. This is miles behind literatures written in, say, Malayalam, Tamil, Bengali, Urdu, or Hindi. To translate at all, and then to translate from an underrepresented language, and finally to translate into English, with all its baggage, is riddled with layers of questions for which there can never be simple answers.

*First published by Sanmingzhi.